(Originally published in theNewerYork, May 6, 2014)

The Da Vinci Code. Hit book and movie series. But there’s also a little-known repository of the master’s documents that have eluded public scrutiny. Until now. And it took the recent discovery of an anatomical oddity in the insect world to bring this to light.

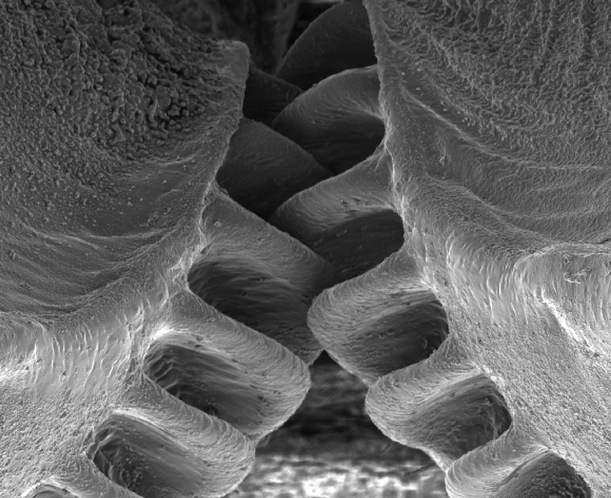

A mechanism on the hind legs of the planthopper nymph are the first known occurrence of a natural expression of what humans consider an invention of our own: a pair of interlocking spur gears. They mesh as the tiny critter is about the jump, thereby synchronizing the spring of both legs for an optimized leap. While the existence of the feature has been known for decades, no one really knew what they were for. Until now.

In response to the announcement of their use, descendants of Leonard Da Vinci argue that the maestro’s considerable inventory of invention should be expanded to include the firsts of bionics (‘Bionico’).

Leonardo DaVinci was obsessed with all things mechanical, and the human body, and now, we know, biomechanics. The master of augmenting human physicality with mechanical and physiological enhancements. And a premier anatomist.

In 1490, a troublesome nephew was hired under the guise of curator of some of Da Vinci’s lesser-known works. In truth, the position was really that of janitor, meant to keep him off the streets of Milan; if he could help tidy up around DaVinci’s workplace, fine. He took to the task with great enthusiasm, and, convinced there was treasure in the maestro’s wastebaskets, would scurry around the studios, shouting at Da Vinci’s minions, ‘Non buttare via!’ (‘Don’t throw away!)

He would come to be known as ‘Nodiscardo Da Vinci’.

It has long been the fashion to view Da Vinci’s renderings in terms of their modern counterparts, his ‘flying machine’ a helicopter, his barrel-array a machine gun, his turreted mega-wagon as a tank. These are the lesser known inventions, for which we have Nodiscardo to thank.

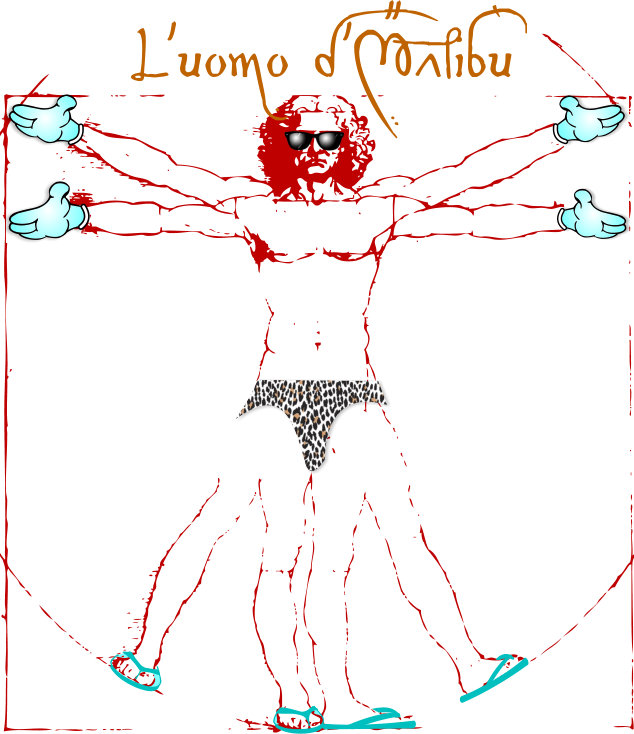

The seminal Da Vinci sketch. However, the more familiar ‘Vitruvian Man’ was actually just one in a series, in which the maestro improved upon the architect Vetruvio’s analysis of the proportions of human physiology by additions of other examples from around the world. ‘L’uomo d’Malibu’ (‘Malibu Man’) is one. This specimen, rescued from a wastebasket, features surgically-implanted cartoon hands, flip-flops, and Wayfarers. And a silk, leopard-print swimsuit.

Notes added in Da Vinci’s hand include this variation on the famous Vetruvian inventory of the human physique, assigned to the Southern California version shown:

A Palm is Three Fingers in a Disneyland Glove

A Foot Must Have Room to Wiggle its Toes

A Cubit is Six Palms Around the Pool

Four Cubits Make a Man Hire a Pool-Boy

A Pace is Four Cubits Lining Pacific Coast Highway

A Man is 24 Palms Waxing His Board

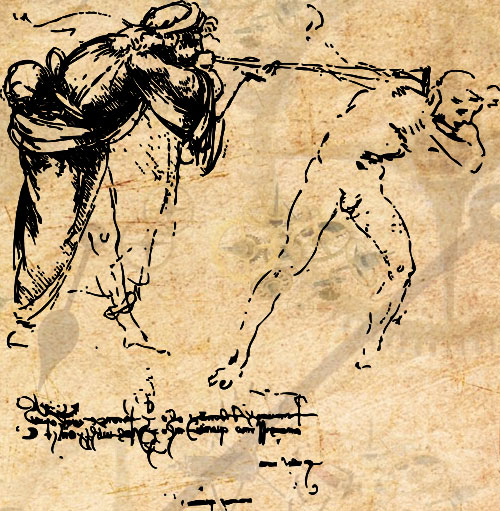

This sketch for ‘Close It!’ (‘Chiuderlo’ )was found, according to a note by Nodiscardo, in a batch of undelivered love-letters his uncle had discarded. The woman referred to was likely Edithora Sforza, the grown daughter of the artist’s patron at the time of her introduction to Da Vinci, and who’s legendary beauty was surpassed only by the incessant talking the artiste came to abhor. ‘Edithora, soffochi te stesso!’ Da Vinci would be overheard muttering whenever she visited his studios. ‘Edith, stifle yourself’ would be famously invoked by the Archie Bunker televison character centuries later, the actor’s homage to the maestro.

This sketch for ‘Close It!’ (‘Chiuderlo’ )was found, according to a note by Nodiscardo, in a batch of undelivered love-letters his uncle had discarded. The woman referred to was likely Edithora Sforza, the grown daughter of the artist’s patron at the time of her introduction to Da Vinci, and who’s legendary beauty was surpassed only by the incessant talking the artiste came to abhor. ‘Edithora, soffochi te stesso!’ Da Vinci would be overheard muttering whenever she visited his studios. ‘Edith, stifle yourself’ would be famously invoked by the Archie Bunker televison character centuries later, the actor’s homage to the maestro.

‘Rule of Thumb’ (‘Regola del pollice’) Commissioned by his friend Michelangelo, who was having fits while laying out his piece for the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. ‘If only I coulda have a tape measure ina my thumb!’ pined Michelangelo, noting that he generally had both hands busy simply holding on to the scaffolding up there. Not a problem for the maestro, who’s solution was thus:

‘Travel with Youth’ (‘Viaggiare con i giovani’) In Da Vinci’s Milan, the elderly were revered. As an homage, a young person was assigned to accompany the city’s senior citizens to market, to prevent the venerable from being hoodwinked by unscrupulous merchants. The maestro describes a procedure for attaching a child to a senior’s hip. (This concept, however, offers some currency to our age. For example, we could attach kids to seniors so the older folks don’t make a mistake at Best Buy, and wind up signing for 2 phablets with an extra phone line on each, a hot spot and a 2TB dataplan.) Da Vinci proposed a simple join-at-the-stomach procedure, which was suggested by the old man shown in this sketch, but which limited the youth’s effectiveness in bargaining with merchants. Or anyone.

‘Travel with Youth’ (‘Viaggiare con i giovani’) In Da Vinci’s Milan, the elderly were revered. As an homage, a young person was assigned to accompany the city’s senior citizens to market, to prevent the venerable from being hoodwinked by unscrupulous merchants. The maestro describes a procedure for attaching a child to a senior’s hip. (This concept, however, offers some currency to our age. For example, we could attach kids to seniors so the older folks don’t make a mistake at Best Buy, and wind up signing for 2 phablets with an extra phone line on each, a hot spot and a 2TB dataplan.) Da Vinci proposed a simple join-at-the-stomach procedure, which was suggested by the old man shown in this sketch, but which limited the youth’s effectiveness in bargaining with merchants. Or anyone.

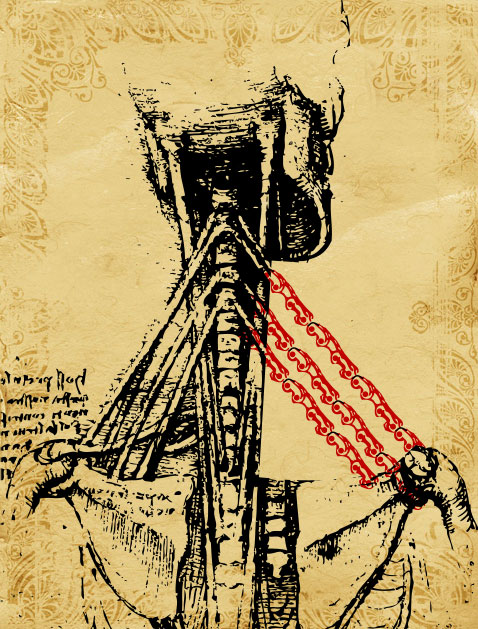

‘Head Holder’ (‘Testa Titolare’) Inspired as a means to help during those drowsy late nights in the studio, Da Vinci envisioned groupings of chains implanted in the shoulders and the neck to help hold his head upright. It was quickly endorsed by the medieval Italian AAA, as a means to reduce the number of chariot accidents on the Appian Way, caused by drivers nodding off on those long hauls between Rome and Brindisi.

groupings of chains implanted in the shoulders and the neck to help hold his head upright. It was quickly endorsed by the medieval Italian AAA, as a means to reduce the number of chariot accidents on the Appian Way, caused by drivers nodding off on those long hauls between Rome and Brindisi.

‘Hearing Aid’ (‘Audizione Aiuto’) It was not obvious at first to the maestro that though the concept of sound amplification to help the hard-of-hearing was a good one, this early sketch showed the folly of having the horn facing in the wrong direction. Not to mention that implantation of horns of this size on both sides of a person’s head proved unwieldy. Lastly, everything presented in the mouthpiece came out as a B-flat to the listener, ruining the message’s conveyance. It would take nearly 150 more years before someone got the idea to turn the horn around, and the ‘ear trumpet’, the world’s first hearing-aid, would appear.

‘Hearing Aid’ (‘Audizione Aiuto’) It was not obvious at first to the maestro that though the concept of sound amplification to help the hard-of-hearing was a good one, this early sketch showed the folly of having the horn facing in the wrong direction. Not to mention that implantation of horns of this size on both sides of a person’s head proved unwieldy. Lastly, everything presented in the mouthpiece came out as a B-flat to the listener, ruining the message’s conveyance. It would take nearly 150 more years before someone got the idea to turn the horn around, and the ‘ear trumpet’, the world’s first hearing-aid, would appear.

‘Bungalow Head’ (‘Testa Bungaloni’) Though this sketch is considered to famously portray Da  Vinci’s design for a parachute (which was proven in the year 2000 to actually work), it was in fact a proposal to solve Milan’s acute housing problem at the time. The homeless were to be equipped with large hats, supported by a special harness fixed to the back and shoulders, that would serve as roofs. Field trials, however, showed that strong gusts of wind would lift the wearers into the sky. The return to the ground, though, was unexpectedly benign. Hence the maestro simply changed the notes accompanying the sketch, and added that the wearer “…will be able to throw himself down from any great height without suffering any injury.”

Vinci’s design for a parachute (which was proven in the year 2000 to actually work), it was in fact a proposal to solve Milan’s acute housing problem at the time. The homeless were to be equipped with large hats, supported by a special harness fixed to the back and shoulders, that would serve as roofs. Field trials, however, showed that strong gusts of wind would lift the wearers into the sky. The return to the ground, though, was unexpectedly benign. Hence the maestro simply changed the notes accompanying the sketch, and added that the wearer “…will be able to throw himself down from any great height without suffering any injury.”

(Modified graphics by the author)