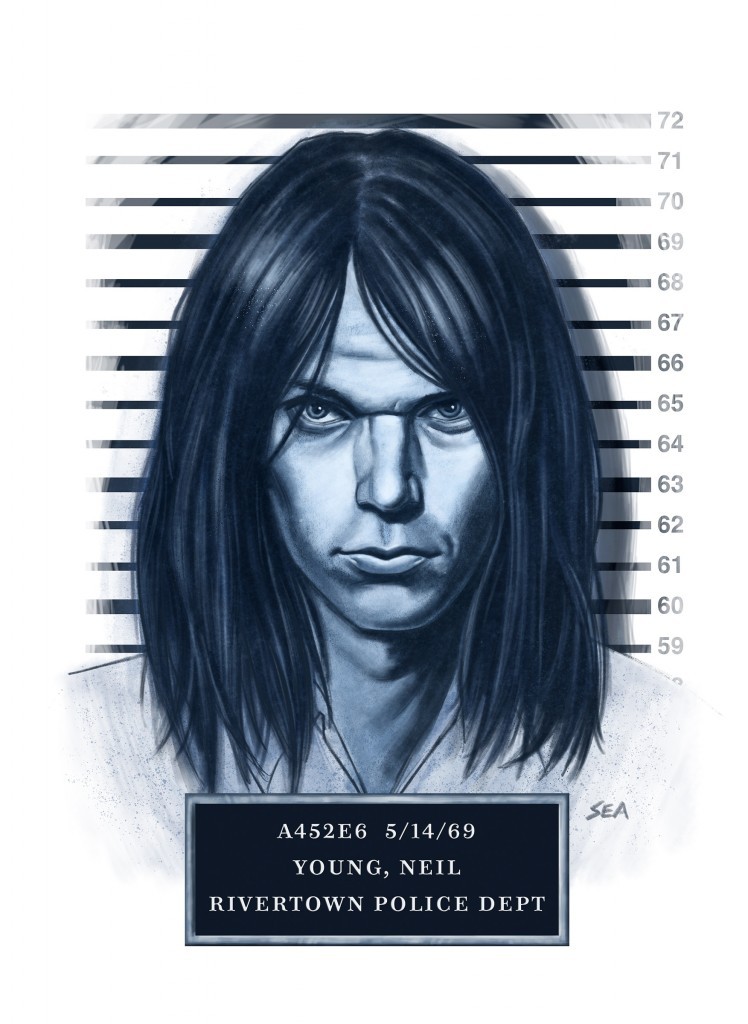

Illustration by Scott Anderson

(First published in North American Review – April 4, 2016)

I’m Denny Pell, and that was the year I changed my last name to Dorito. Legally. Because I could. I was a newly-minted lawyer then. And I liked the word. I liked filing the papers.

While I’ve always liked the popular snack food, I was more interested in its origin, from the Mexican-Spanish ‘doradito’ or ‘golden boy.’ I was fresh out of law school and on my way to make my fortune, and this name, I thought, would be good luck.

The change got me into trouble fast. No one would take me seriously. I should have expected that. Dating was a nightmare. Women were reluctant to hold my hand for fear that I would turn their fingers orange.

“I’m Cool Ranch,” I would say, “not Nacho Cheese.”

“Yellow fingers, white fingers, it’s gooey cheese gunk all the same.”

My first name is actually Eldon, or ‘Denny’ to my friends and throughout my school years. Now I chose to resurrect my other nickname, the one my father had given me in childhood, ‘El.’ When jokes about snack foods rose to a fever pitch, I took to calling myself ‘El Dorito.’ This suggested the mythical Mexican town, ‘El Dorado.’ That helped.

Soon, everyone just called me ‘El.’

I needed my ‘pay dirt’ case, one that would set me up for life, and allow me the time and resources to take on the pro bono cases and do the Lord’s good work. Unfortunately, all the tobacco and air bag and asbestos cases had been taken on by the big firms.

I got an idea.

“Neil Young got away with murder,” I told a friend I’d taken the bar exam with. “I intend to see him pay.”

“What did he do?”

“Shot his baby. Down by the river. Then wrote a song about it, and played it for all the world.”

“What about Jimi Hendrix? Didn’t he shoot his old lady down?”

“Yeah, but Young is still alive. I can make a career on that. And Hendrix didn’t actually shoot his old lady, the song was an interview with someone named ‘Joe,’ he did it.”

“Which made him an accessory, right? Because of the knowledge he had of the homicide? If he did nothing about it. And there’s nothing in that song to say that he did.”

“Yeah, but Jimi Hendrix is still dead, and what you’re saying doesn’t change a thing.”

Before long, I rented a Malibu and was on my way to the little town in the Heart of the South where he shot her. The entire town was a living tribute to the guy and the song ‘Down by the River.’ The song in which Young confessed to the crime. And for which I was determined he would pay. Not criminally, although why he was never arrested and charged for that bothered me.

No, I was going for the civil case. Wrongful death. There’d be a settlement in that.

In the early 1970s when the song came out, the town changed its name to Rivertown. To this day, the town is frozen in that time. It’s a college town, home to Rivertown Polytech. Many of the residents wear plaid flannel shirts, jeans, and work boots. Many of the men wear their hair shoulder length, parted in the middle, and some of the women look like Joni Mitchell did back then. Young and old alike. Not Neil Young, actually ‘young.’ The old dress like this because they’re frozen in time and know nothing else. The younger do because they know nothing else, either.

The streets are named for Jackson Browne and Richie Havens and members of Crazy Horse and the Eagles and Carlos Santana’s band. And all five of the Jacksons. The Jacksons back then. There are only four now.

The people in Rivertown were noticeably thinner than people are anywhere else. They smoke everywhere, some wear puka-shell necklaces, almost everyone a bracelet braided from string or rawhide. The gas stations sell no snacks. They weren’t known for that yet. I found Doritos for sale at a corner grocery, but they were the pointy-type, and just the original corn flavor. Just like when Neil Young first played here, at the Student Union. He put seventeen grand in the pocket of his jeans for the night’s work. Those were 1971 dollars, btw, about 100 thousand bucks today. And, Nacho Cheese was not yet widely available then. Even Neil Young couldn’t have bought a bag of those no matter how much he had in his pocket. This guy who shot his baby.

On the sidewalk outside the storefront with a plate-glass window lettered ‘Black Panther Party’ were several milk crates, an ashtray on one, but no one was around.

I paused there on my tour of the town, and thought about how handy milk crates were.

Then I noticed that the crate with the ashtray had five, maybe six of what looked like ankle monitors in a little heap. The bands had been modified with a clasp for easy on and off. The plastic housing could be opened from the top, into which a Zippo lighter was shown to fit in place of the electronics. A hangtag on each read ‘Donation $5.’ Below, in small print, it read ‘Lighter Not Included.’

Rivertown is in the South, in the ‘Heart of the South.’ The South is the only place in the country that has a Heart. The only place with any anatomical reference, really. There’s no ‘Belly of the North’ or ‘Legs of the West.’ There’s even a Deep South. No other place has a ‘Deep.’ There’s no ‘Deep Southwest’ or ‘Deep New England.’ That I know of.

Rivertown is in the South, in the ‘Heart of the South.’ The South is the only place in the country that has a Heart. The only place with any anatomical reference, really. There’s no ‘Belly of the North’ or ‘Legs of the West.’ There’s even a Deep South. No other place has a ‘Deep.’ There’s no ‘Deep Southwest’ or ‘Deep New England.’ That I know of.

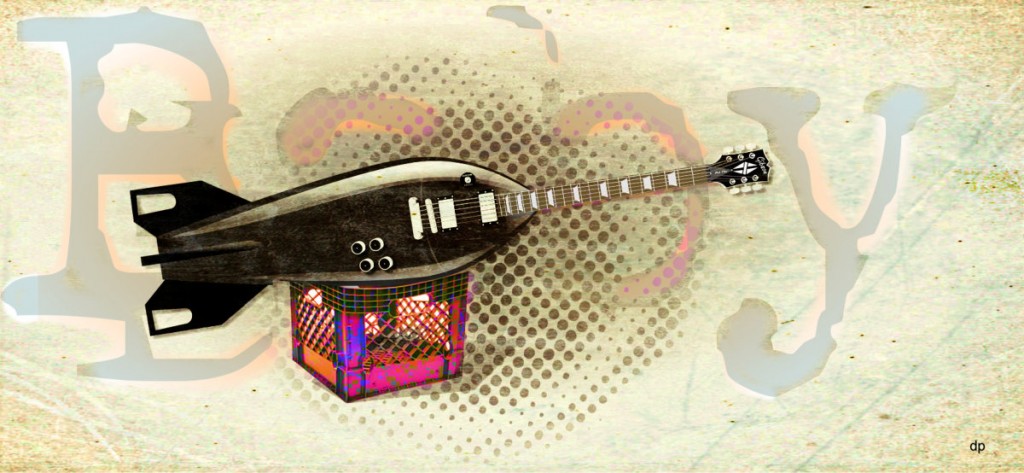

There was a music store in town that advertised guitar lessons in the window. There was a picture of one of Neil Young’s Stratocasters. Beneath that, ‘You’ll Solo in One Day.’

I always wanted to play the guitar, but really went in because the promise in this advertisement was clearly a hoax. And maybe I could make a career on that, too. Grab these people up into some class action.

“One day to solo?” I asked the hawk-faced man behind the counter sorting 8-track tapes into milk crates stacked along the back wall.

“One day. Most are good to go in one afternoon.”

“How can that be? How can I solo in one afternoon?”

“Because I’ll teach you to play like Neil Young.”

“What? In one day? How?”

“Because you’ll learn the solo from ‘Down by the River.’ And it’s just one note. Mostly. At some point, there’s two. Two notes.”

“Well, there. You just said it. If I recall the solo, there’s a couple of them, notes, you know? He does wander off into certainly one other note, and then a few more. So you’re saying you can teach me all that in one afternoon?”

“The other note, the other major one, and those few more you mention. That used to be the Advanced Solo Class. But now we include it. People learn faster now. We throw that in at the end of the main class. We used to charge for it. But now it’s included. No charge.”

I noticed the poster on the wall above the milk crates. It too said ‘No Charge.’ For guitar lessons ‘for any Wounded Warrior.’

“We’ll teach you a good solo,” he went on, “An honest riff, not showy, self-aggrandizing, and masturbatory like so many guitar rides are. In that song, he’s alone with his thoughts and feelings and invites the listener to be, too. That’s what ‘solo’ means.”

“Seems pointed, abrupt . . . almost angry, that stark, staccato pace and tone.”

Kind of what you’d expect, I thought, from a guy who’d just shot his baby.

“As said, your thoughts and feelings,” the man said. “We don’t just teach guitar here, we work to make you a better person. Here, put this on.”

He handed me a vintage black Gibson Les Paul. It slung low, comfortably, in a way I didn’t even know I liked, but I did. And I don’t even play guitar.

“What are you feeling?”

My left hand found the neck, my fingers the strings. “It’s . . . I’m . . .”

“Go with it.”

“Well, it’s like I know what people are feeling. Like what you’re feeling right now. That you’re kind of . . . is it happy? For me? It’s . . . ‘empathy,’ if I had to come up with a single word . . .”

Any Wounded Warrior, I thought.

Later, I was on my way back to my hotel. It was down at the end of Lonely Street. But I missed the fork in the road. As I rounded a curve and the building came into view, I stood both feet on the brakes of the rental car. I knew that facade, the late deco style of the soaring glass and aluminum entrance and the glazed, blond brick of the exterior.

I remembered my father’s accounts of the Congressional hearings in which he, Carter Pell, intern to Senator John Tower, had participated. I remembered nothing of what he told me about the hearings other than one of the exhibits, a photo of the ‘UXB, Inc.’ plant which Dad had framed and hung on a wall in our living room. And this was the building I was now stopped in front of in that sharp light of a late afternoon in the Deep South.

It happens that the main industry in Rivertown had been uxb, Inc., a company which was years later found to have supplied unexploding bombs to the Vietnam war effort. It occurred to some at the time that you couldn’t possibly drop what would amount to 7 ½ million tons of bombs on a country the size of Vietnam and still be losing the war. A lot of these had to be duds. Something Senator Tower was keenly interested in exploring in his subcommittee hearings.

Turns out that as the antiwar movement was ratcheting up, inside the government a secret antiwar group within the Pentagon had decided to mix the unexploding bombs in with the real ones on the advice of sympathizers at the State Department. This way, the citizens could have a source of income after the war, digging the fake bombs up and selling them as collector’s items. The bombs would be substantially real, including gluey packings that mimicked high explosives, and detonators that whirred and ticked when disturbed. This was to keep the disposal units on their toes.

UXB, Inc. even employed an art department, which decorated the non-bombs with chalked outlines of genitalia and epithets in both English and Vietnamese, just like crews on flight lines always do in war.

The next day I drove my Chevy to the levee.

The gps guided me to a place down by the River where, in the song, it had happened. A bronze plaque on a metal post marked the site, a public park named ‘Down by the River.’

It was a pleasant place, behind the shady trees. The River was broad here, flowing slowly, its smooth surface dappled by early afternoon sun.

I toyed with the idea of digging the Les Paul and the small portable practice amp I’d purchased with it out of the trunk, and setting up to practice the solo in this setting. Then I heard soft guitar music from an empty, open-air theater nearby.

There was a young man sitting on the edge of the stage humming along to a song I felt I knew. Alongside him was a young woman. They were a couple, and had left their childhoods behind, not as long ago as I had. They were friendly, and I thought, old-fashioned.

Her hair was curly, short on the sides, long in back, teased bangs piled high in front.

She said her name was Diane. Diane Cayenne. It was originally Diane Cinnamon. Her mother was the Cinnamon Girl in the song of the same name. And she’d been in the movie Grease. She was a dancer, Diane said.

“This is Jack,” Diane beamed. “My fiancé.”

The young man held out his hand. “Nice to meet you. I’m Jack. Jack Suthern.”

“You’re a . . .”

“A Suthern man,” he winced.

Attached to the apron of the stage next to them, and extending out from below it, was an odd set of metal steps. I just had to know what they were. Jack demonstrated the scissoring action by which the steps were extended, then compressed backwards out of the way neatly, when no longer needed.

“I invented them for Diane. She’s always had trouble getting up here,” Jack explained.

“Yeah,” she said, “we used milk crates before, but they were always so . . . wobbly.”

“You should market these,” I said.

The young man nodded, “Yeah, well, Johnny Mathis sang here last year, and his road manager saw them, so I gave him a set for Johnny’s tour bus. We’ve been getting orders since

. . . Kiss, Garth Brooks, Dolly Parton, Cirque du Soleil . . .”

“Our French language version,” Diane chimed.

“Diane handles the marketing,” Jack grinned, pecking her on the cheek.

“I got Professor Fabre from Poly to translate the instructions into French,” she said. “We were hung up for days on the word ‘retractable.’ It seems that’s not a concept the French understand. So we had to go with ‘extensible.’ Or, shall I say ‘ex-ten-see-blay.’

By the look on my face, I was struggling.

“A ‘thing’ does not retract from a Frenchman,” she said. “How dare it? They are the center of everything, the French. So, things extend to them.”

“Still don’t have a name . . .” Jack pined.

“Extensible, retractable . . .” Diane hummed.

“And now there’s the nasty letter we got from a folding-bleachers manufacturer last week, about, maybe, patent infringement . . .” Jack strummed a few chords softly, looked up, “Do you know a good lawyer, Mr. Dorito?”

“El is fine, Jack.” I said I did. Then, to my astonishment, I asked if I could join in, making a guitar-playing motion with my hands. Jack was thrilled. I wanted to sling that Gibson low and feel those things I’d felt in the music store. That empathy. And I wanted to solo.

No sooner did I strap up did I know much more about the quiet ease they shared in each other’s company. It spoke of a long courtship and memories of picnics and rodeos and church choirs and steamy nights on tufted vinyl backseats pawing at the shyness of their shared youth, anointing the end of their innocence with a froth of sweat and fluids.

Jack pulled up the leg of his jeans and fished a Zippo out of an ankle bracelet. He lit a cigarette, offered me one. I declined. He took a drag and stuck it, filter-first, under a string near the tuning pegs on his guitar. He never touched it. It burned down to the filter while we played, the way that some guitarists do. I liked that about him. We jammed till after sundown. Me and Jack. And Diane on tambourine.

Milk-crate steps enjoyed a special place in popular RV culture, and for decades had a lock on that market. Ever since John Kennedy selected one to enter and exit his bus in his ‘60 presidential bid. From that moment on, it became the symbol of electoral humility for all candidates, and the first choice for the new owners of RVs in the fledgling motorhome industry. Every RV sold for decades included a milk crate step, which one set out upon parking.

Students found they were perfect for storing record albums. Long before ‘branding’ was the holy grail of marketing, some artists ‘branded’ milk crates just to store their albums. Neil Young had his own line for a while. He called them ‘Harvest Crates.’ What balls. He got away with that, too.

Of course, community groups had long since found them useful as temporary sidewalk seating, and they were perfect for 8-track storage in retail applications. The milk crate industry would not be hurting long, and soon, new markets and applications developed.

I made a career of representing Jack and Diane and their folding RV stairs company, ‘The Extensibles.’ With grants from the government, we were able to set up shop in the old uxbplant. We went global.

I’ve spent all these years as a lawyer in Rivertown, which was its name until just recently.

One day, I was on my way downtown for a meeting with the Black Panthers. I do some pro bono work for them now and then. I support other causes, too.

Anyway, that day there was a long line of cars at the gas station, reminding me of pictures my dad had shown me of the oil crisis of 1973. This time, it wasn’t for gas, but a queue for the charging station. The cars in the line moved silently forward, eerily, as they were all electric.

People are known to offer to keep a place in line for a price, and people are known to pay it. The day before, two guys duked it out, and were arrested. Just like in ‘73. People don’t like to wait in line to make their cars go, no matter which century it is.

I was picking my way around the cars, when a guy rolled down his window, “Excuse me, can you tell me where I am? My gps seems confused.”

“You’re at Main Street and Jermaine,” I said.

The man mouthed ‘Jermaine,’ with a puzzled look.

“Jackson,” I offered.

“No, I mean where. Isn’t this Rivertown?”

“No more. Name was changed last month. By City Council.”

“Why?”

“Bad press. This is ‘Ektin’ now.”

“Ektin?! You mean like the city . . . in . . .over in . . .”

“Nepal? Hah! No, we’re the other Ektin. The American one.”

“Odd name. What does it mean . . . Ektin?”

“Everybody knows this is nowhere.”

(‘Baby’ graphic by the author; Neil Young illustration by Scott Anderson )